March 30, 1849. At a secret location in Philadelphia, a box arrives, measuring 3 feet by 2 feet. Inside is fugitive slave Henry Brown.

Shipped from Richmond, Virginia, 27 hours earlier, he escaped with help from men on both sides of the racial divide.

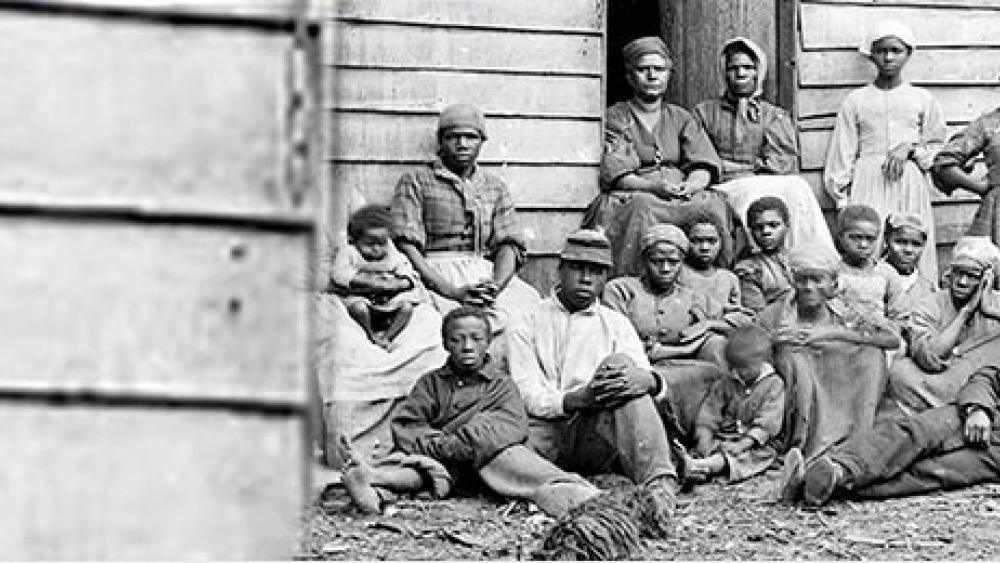

"The Underground Railroad was collaborative," Dr. Cassandra Newby-Alexander, director of Joseph Jenkins Roberts Center for African Diaspora Studies, said.

CBN News met with Dr. Newby-Alexander in her office at Norfolk State University.

"You needed partners, you needed blacks and whites working jointly together to help people escape from slavery. People have seen the Underground Railroad as the first integrated resistance movement," she said.

The Underground Railroad

Anyone involved faced great risk. If caught, slaves were severely beaten and in some cases executed. Free blacks were sold into slavery.

In the case of Henry "Box" Brown, he got away. But the white man who helped him in Richmond served over seven years in the penitentiary.

"If you assisted someone to escape from the Underground Railroad, and you were white, you were seen as a far greater threat than a free black or an enslaved person," Newby-Alexander explained.

"And so the punishment was extremely severe," she continued. "In 1850 and 1860 you can look at the census records and see how many people were in the Virginia penitentiary with the charge that they were helping someone try to escape."

She showed copies of pages from the 1850 census. In the column where the crimes are listed, there are several entries saying "advising slave to run."

But many were willing to take the risk, especially at the Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. It was a key location in the Underground Railroad. Most fugitive slaves escaped from the upper South, particularly Virginia and Maryland.

The Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1775 with members of both races. By 1838 they had their own building, called Pennsylvania Hall. But it was burned to the ground after just three days, forcing them to go undercover.

Society member William Still kept extensive records and published them after the Civil War in a book titled The Underground Railroad. He gives numerous examples of fugitives getting help -- in the form of homes, job training, money, even clothing.

"By the 1830s, the northern factories were pumping out a type of cloth that was used in slave clothing, so you actually were branded by the clothing you had," Newby-Alexander explained. "So one of the first things you wanted to do, once you got to the North, is change your clothes."

Abigail Goodwin donated her best clothes.

"[Her sister] has often said that few beggars came to our doors whose garments were so worn, forlorn, and patched-up as Abby's," Still wrote.

The 'Seekers of Light'

Like a great many white abolitionists, Goodwin was a devout Quaker.

"Originally they called themselves 'Seekers of the Light.' But they were given the name of Quakers because it was said that they 'trembled at the Word of God," Mike Richards, a lifelong member of the Friends Meeting in Camden, Delaware, said.

They eventually became known as the "Religious Society of Friends." Their meeting house was established in 1795, and its members were active in the Underground Railroad.

Richards explained the Quakers' battle against slavery came from core beliefs, originating with founder George Fox.

"He came to the belief that there was that of God in every person. That's the wording that he used, 'There is that of God in every man,'" he said.

In 1688, Quakers signed the first anti-slavery resolution in the American Colonies.

"The most important thing about Quakers is that you live your values," Robin Krawitz, director of the Historic Preservation Graduate Program at Delaware State University, said.

"They tried to do that in every aspect of their lives, whether it was buying produce that was not made, grown, or created by enslaved people; whether it was wearing garments that were not produced from cotton," she added.

Meager Beginnings

CBN News spoke with Krawitz at the Appoquinamink Meeting House, which was built in 1785.

Just 20 square feet, it is presumably the smallest brick house of worship in America. But the Bible says, "Despise not small beginnings, for the Lord rejoices to see the work begin." (Zech. 4:10).

"This was a preparative meeting, which meant that this was where people came weekly for their worship," Krawitz explained.

Except for the addition of electric heat, the meetinghouse is unchanged since 1785. In the attic, where children met for Sunday School, sit the original little tables and chairs.

There is a panel that opens to reveal a hiding place for runaway slaves, confirming its designation as a station on the Underground Railroad. It has also been said that Harriet Tubman stayed there.

Tubman collaborated often with Thomas Garrett, a member of the Appoquinamink Meeting. Garrett helped more than 2,000 runaway slaves make their way to freedom.

His home was put up for auction after being fined heavily.

"Thomas, I hope you'll never be caught at this again," the sheriff told him.

Garrett's reply was typical of most agents in the Underground Railroad: "Friend, I haven't a dollar in the world, but if thee knows a fugitive who needs breakfast, send him to me."

This story was originally published on Feb. 4, 2021.

***As certain voices are censored and free speech platforms shut down, be sure to sign up for CBN News emails and the CBN News app to ensure you keep receiving news from a Christian Perspective.***

Did you know?

God is everywhere—even in the news. That’s why we view every news story through the lens of faith. We are committed to delivering quality independent Christian journalism you can trust. But it takes a lot of hard work, time, and money to do what we do. Help us continue to be a voice for truth in the media by supporting CBN News for as little as $1.

Support CBN News

Support CBN News