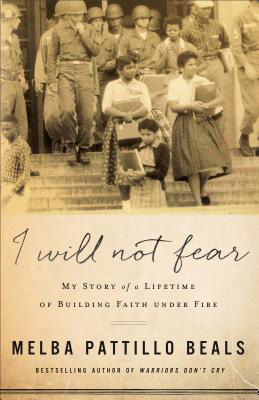

Building Faith Under Fire

INTEGRATION OF CENTRAL HIGH

Melba was one of the Little Rock Nine – nine African American children (Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Gloria Ray, Thelma Mothershed, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, Carlotta Walls and Melba) selected by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. She hoped attending the prestigious school would provide an opportunity to get a scholarship to one of the top universities in the country.

The night before they were to go to the school, Governor Orval Faubus posted Arkansas National Guard troops around the school to prevent the Little Rock Nine from gaining entry. Fifteen-year-old Melba and the others endured shouting, angry, rock-throwing mobs who were determined to block them from the entryway to the school. Melba realized she was in great danger when she understood the mob wanted to kill her and her mother. To escape, they ran down a path only steps away from their attackers. Melba called out to God, “Please, God, please!” The unpaved path ahead of them had dead tree branches which Melba and her mom avoided by going around them. The men behind did not see the branches and tumbled over each other. Their fall gave Melba and her mother the few seconds they needed to get away in the car. For the first time in her life, Melba felt a direct connection to God. Eventually, President Dwight Eisenhower replaced the National Guard with the 101st Airborne who escorted the Little Rock Nine into the school to enforce a 1954 Supreme Court order that schools integrate “with all deliberate speed.”

After attending Central High, Melba’s carefree childhood was no more. The Ku Klux Klan rode around her neighborhood at night threatening people because they wanted to attend the school. Melba recalls, “Shots rang out, and bullets pierced our window.” She was forbidden to leave the house unless appropriate adult escorts were available. During this challenging time of violence and fear, Melba relied on God.

LIFE AFTER LITTLE ROCK

Melba’s grandmother encouraged her to be grateful for each day. The hardest part of her grandmother’s instructions was to forgive those who mistreated her at school. Meetings with the dignitaries of the NAACP from all over the United States took place on a regular basis. Melba recalls one evening when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. attended. At this point, she was three weeks into the semester at Central High School. Exhausted, depressed, and disappointed, Melba poured her feelings out about how she was suffering to Dr. King. His response, “Melba, don’t be selfish. You’re not doing this for yourself. You are doing this for generations yet unborn.” His voice was kind and empathetic as he went on to explain the nature of a God-assigned task.

As the death threats from the KKK continued to mount, the NAACP and her parents decided she would leave Arkansas to save her life. The NAACP solicited members in branches across the country to take in and protect the Little Rock Nine. Melba went to Santa Rosa, California where she would be staying on a farm with a white Quaker family called the McCabe’s. At first, she was afraid and lonely not knowing what to think of this white family who took her in. Day after day they taught her the meaning of kindness, acceptance and love. She attended Montgomery High School with four other African American students. The big difference at this school was that some of them smiled and no one reached out to hit her. In fact, none of them called her names or made rude gestures. The McCabe’s became parents to Melba and taught her that white, a word Melba often substituted for freedom, was a state of mind and freedom was hers to choose.

At nineteen, Melba was living on her own with a roommate while attending San Francisco State University. She met a white soldier named Jay. Although she insisted that she didn’t date white men, Melba felt very comfortable around him and before she knew it they were married in Reno, Nevada. Soon after they married, Melba became pregnant and quit college. Her mother in Arkansas was angry with her for marrying a white man and for quitting school. After a year passed, being a wife and mother was not enough for Melba. She longed to go back to school to complete her bachelor’s degree. Jay wanted her to focus on being a housewife. The conflict led to unhappy days and miserable evenings. Melba developed bleeding ulcers and even had a miscarriage. Although she loved Jay and wanted to keep her family together, she felt like she was becoming someone she didn’t know. Ultimately, Melba says, “It was our cultural differences and expectations that led to our divorce.”

MELBA’S CAREER

As a single mom, Melba and her daughter endured many financial struggles while she worked to complete her degree. When she finally received an internship for the local CBS television newsroom things began to look up. She also was selected into the Columbia University New York program in broadcast journalism. The program was for thirty-five minority students from across the United States who would be trained in television news and granted full-time jobs in the industry when they were finished with their graduate degree. The scholarship was a kick start to her career. Melba gained a job on public television as a journalist and within a couple of years later, she was employed in the seventh largest television market in the nation at NBC in San Francisco. A year later, she was offered a job at KRON TV, NBC’s local affiliate. She became one of the first female reporters in San Francisco and the first African American granted the post of an on-air news reporter with a major network. Although people were recognizing her, asking for her autograph, and requesting her for public appearances Melba noticed that she still faced racial prejudice in the workplace. Throughout her career as a public relations specialist, professor, and a businesswoman Melba has often encountered segregation, separateness, and oppression but she relies on her faith to carry her through as she continues to forge a trail for others to follow.

At fifty, Melba adopted two three-year -old boys. Raising them was a daunting task that tested her physically, spiritually and mentally. She says, “Adopting my twins made me a better Christian, a better teacher, and a better human being.” Today her sons are college graduates and she says, “There is nothing to replace the joy, peace and pride I have in my sons.”

The Little Rock Nine went on to accomplish great things in their professional careers, some of them serving in the areas of higher education, mental health, and the criminal justice system. In 1999 President Clinton awarded the Little Rock Nine with the Congressional Gold Medal for their important role in the Civil Rights Movement. Ten years later, President Barack Obama invited them to his inauguration. Last year marked the 60th anniversary of the integration of Central High.

After retiring in 2014 from her post as a university professor, Melba underwent three spinal surgeries. During rehab Melba held on to her faith. She says, “Struggling to maintain my sanity was the most difficult task I had ever encountered.” Melba is thankful that God kept his promises to her.